DAAD Lectureships

DAAD Lectureships are usually set up at the request of a foreign university and in consultation with the Federal Foreign Office. The foreign university provides a corresponding position and remuneration for a lecturer and, in coordination with the DAAD, formulates the lecturer’s tasks and required qualifications. The DAAD looks for suitable candidates and proposes them to the university. In addition to the role of mediator, the DAAD also takes on promoting and supporting functions.

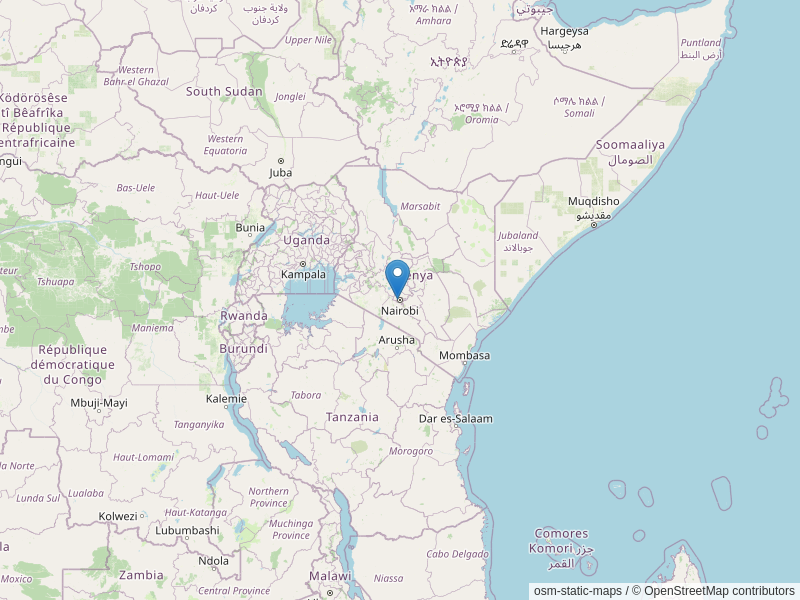

There are currently five DAAD lecturer posts in East Africa, and only two are currently occupied: in Kenya, the Nairobi University (currently vacant) and Kenyatta University, in Ethiopia Addis Ababa University (currently vacant), in Uganda Makerere University, in Tanzania (currently no university affiliation).

The DAAD Lectureship at the University of Rwanda was closed in 2021. The University of Rwanda is no longer interested in the lectureship.

Here you can find the experience report of Dr. Rainer Schmidt, DAAD Lecturer at the University of Rwanda from 2016-2021:

Please introduce yourself:

My name is Dr. Rainer Schmidt, a political scientist with a doctorate and habilitation, currently on a DAAD return grant at the University of Bayreuth (Prof. Dr. Alexander Stroh/African Politics)

Please tell us more about your time as a lecturer in Rwanda: how long were you a DAAD lecturer at the University of Rwanda? What teaching assignments, activities, and research did you do? What were your experiences at the faculty with colleagues students?

I was a DAAD lecturer from September 2016 to August 2021 at the College of Arts and Social Sciences (CASS) at the University of Rwanda (UR). There I taught in all political science areas and gave a few courses for historians. This is mainly because the title of my lectureship was: “Culture of Remembrance.” For this reason, I was especially involved with my colleague Prof. Charles Kabwete, a historian and now Dean of the College. I also successfully applied for a research project together with him at the Gerda Henkel Foundation. The project was about returning skulls and bones (human remains) from Berlin stocks to Rwanda. These were mainly brought to Germany during one of the colonial expeditions in the first decade of the 20th century. We will soon engage ourselves with the return of these remains and, above all, with the celebrations and the questions on remembrance culture that may arise from it.

I was a DAAD lecturer from September 2016 to August 2021 at the College of Arts and Social Sciences (CASS) at the University of Rwanda (UR). There I taught in all political science areas and gave a few courses for historians. This is mainly because the title of my lectureship was: “Culture of Remembrance.” For this reason, I was especially involved with my colleague Prof. Charles Kabwete, a historian and now Dean of the College. I also successfully applied for a research project together with him at the Gerda Henkel Foundation. The project was about returning skulls and bones (human remains) from Berlin stocks to Rwanda. These were mainly brought to Germany during one of the colonial expeditions in the first decade of the 20th century. We will soon engage ourselves with the return of these remains and, above all, with the celebrations and the questions on remembrance culture that may arise from it.

In the beginning, the DAAD’s tasks mainly revolved around making inaugural visits and presenting and publicizing the work of the DAAD. I was the first representative of the DAAD in the country. In the beginning, the focus was on the government scholarship program, and later on, Falling Walls events, countless personal conversations with colleagues from public and some smaller, private educational institutions. In the early years, numerous delegations came, especially from Rhineland-Palatinate, which has special ties to Rwanda. But I would also like to highlight the excellent cooperation with the other German institutions: with Katharina Hey from the Goethe Institute and Oliver Dalichau from the Friedrich Ebert Foundation. And at the end, of course, not to forget memories of our lectureship group, with the wonderful conversations and trips to South Africa and Uganda.

What motivated you to join the DAAD lectureship and especially for the lectureship in Rwanda? How did that happen?

I had already dealt with themes of memory as part of a large collaborative research center with the unwieldy title “Institutionality and Historicity.” This came from my time in Dresden (TU Dresden), where I was an assistant professor for political theory and the history of political thought from 1994 to 2009. Then I was also involved with the topic again in Brazil, where I held the MartiusProfessorship for Germany and European Studies (DAAD) from 2009 to 2014. From this time, a volume was published in Portuguese as a reminder in the social sciences. When a specialist lectureship job dealing with this was advertised in Rwanda, many things fit together.

Rwanda’s political scene and the culture of remembrance are exciting; would you like to report on them?

Of course! I could write a novel on this! The most important thing is undoubtedly to point out the connection between remembrance and reconciliation. A country that has lived through such traumatic experiences and is still marked by this phase of a total loss of order and trust cannot free itself from this burden within a generation. The reconciliation phase is a process. It started back in 1994/95 and deserves every respect from outsiders. But it’s far from over. It will be left to future generations to slowly and gradually work through the gaps still opening up. National remembrance is increasingly accompanied and commented on by a global public. This stage offers proliferous opportunities and several open questions: who is allowed to participate in this conversation and under what circumstances, and whom will they represent?

What were your highlights in Rwanda? And the low points?

The highlights were undoubtedly the beautiful conversations with the students inside and outside the classrooms and the warm, collegial relationship with colleagues.

The highlights were undoubtedly the beautiful conversations with the students inside and outside the classrooms and the warm, collegial relationship with colleagues.

I also don’t want to forget the many trips around the country. Although Rwanda is a small country, it has beautiful travel destinations with national parks. I’ve always loved going there.

The low point was the beginning of the Covid pandemic. Unfortunately, it was impossible to do online teaching in a significant way. With the onset of the pandemic, good, satisfying work, both in teaching and in research, was no longer conceivable. Additionally, I have to say that the topic of plagiarism on the part of the students accompanied me in a very stressful way right from the start. I wasn’t prepared for that.

What are your favorite memories from your time in Rwanda?

I remember the friendships that developed in Rwanda most fondly, as I mentioned earlier. I am looking forward to seeing many of the people I grew fond of when I go back there this year – for the research purposes mentioned above.

But I’m also looking forward to strolling through Huye, my university town in the south of the country, and I’m excited to see what will have changed. Does the only local Chinese restaurant with its great green beans still exist?

But I’m also looking forward to strolling through Huye, my university town in the south of the country, and I’m excited to see what will have changed. Does the only local Chinese restaurant with its great green beans still exist?

How has this experience shaped your professional and personal life?

In any case, I will remain scientifically loyal to the East Africa region. I am yet to see what can develop from this. In any case, I advise everyone who studies politics to teach and live south of the equator for a more extended period. For very understandable reasons, many things are seen, evaluated, and discussed completely differently in Africa. I had already learned the first lessons from Brazil, but Rwanda once again broke the thought patterns that I had taken for granted. I found that to be very exciting.

Thank you for the interview, and all the best for the future!